How has art been a form of protest? The story of Gran Fury

- Amy Lee Lillard

- Nov 12, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Dec 16, 2025

Can art be a form of protest? Does art really work as resistance? And how can you make protest art?

In times like these, it's natural to wonder if art is really important. If writing, music, performance, and other creative work really matters.

I find hope and inspiration from looking at stories of artists using their work to resist the status quo. The story of Gran Fury and ACT UP is a super powerful example to show the way.

Listen to this story:

For each of the artists, it started with a death. Someone close to them - a partner, a friend – died from a terrifying new disease. There was no help, no meds, no cure.

And no one seemed to care.

Politicians ignored the sick and dying, or even explicitly said they deserved it. Doctors and nurses refused the disease, quarantining or completely leaving patients alone to die. Even people in the queer community refused to acknowledge or discuss the new reality.

And that was…enraging.

When would it stop? How would it stop? Would it stop?

A few men started gathering in the West Village, just to talk about this new reality. To cry about their lost loves. To admit their fears and hopes and deep, unrelenting anger.

And then – they couldn’t be silent anymore.

How did a handful of artists kick start and script a seismic shift in AIDS awareness and policy? How did their creative skills drive a movement? And what can we learn from the story of Gran Fury about how to make art as resistance today and tomorrow?

From Rebel Yell Creative, this is The Art of Resistance, a podcast about channeling our rage into creation, and using writing, music, and all kinds of art to resist the status quo.

I’m your host and producer Amy Lee Lillard, and I’m an author, podcaster, and queer GenX woman raised under the specter of AIDS. I’ve been obsessing over artists who resisted since I was a kid. And today, I’m looking to make all the weird art, and help others do the same.

PART 1: GRIEF AND SILENCE

In 1984, just a few years into the AIDS crisis, Avram Finkelstein lost his partner to AIDS. He was devastated, and he was also scared. Could he have the disease too? No tests existed yet, and even if they did, a positive diagnosis would just be a death sentence, with no treatments available.

Avram’s friend Jorge Socarras had also just lost his partner. As the cases had tripled and tripled again each year, he’d kept a list of his friends that died. By the time it reached 100, he was desperate for something to change.

They started meeting for dinner, to get out of their apartments, to talk about their grief. To feel human for a few hours.

And to talk about the disease, in ways they hadn’t done before. Avram and Jorge talked with disbelief, with confusion, and with anger about the misinformation everywhere. The complete lack of any treatment, or hope for one. They talked about how Jesse Helms and other politicians said the gays deserved what they got. They talked in frustration about how even other gay men wanted to ignore what was happening.

Over time, a few more men started showing up to dinner. By mid 1985 they were having regular potlucks.

At each dinner, the conversation grew. The anger grew. AIDS was consistently being portrayed in the media as a gay disease, as these men saw how this lifted the veil from the barely-veiled homophobia among politicians, doctors, and every day Americans.

Queer rights in the U.S. had been on massive whiplash through the 20th century. In the 1920s and 30s, queer actors, artists and musicians were the ultimate celebrities, part of a so-called pansy craze. Then just a few years later, the Lavender Scare of the 1950s swung hard to the right, as the U.S. government worked to root out all queer people from their jobs, their homes, even their lives.

The sixties civil rights and feminist movements encouraged the queer community, and particularly trans women, to fight back against police raids and discrimination at the Stonewall Inn in 1969. After that, the 1970s showed some loosening around laws and opinion of LGBTQ Americans.

But in 1980 – Ronald Reagan became president on the back of the evangelical right, bringing with it a wave of religious and corporate repression. There was a massive backlash to the women’s rights movement, to civil rights, to workers’ rights, and to any understanding or acceptance of gay Americans. The resulting environment was one that seems very familiar to today.

In 1981, the first New York Times article about the disease talked about a “rare cancer” seen in 41 homosexuals. It didn’t have a name, let alone a test.

As the disease spread quickly among gay men, but also intravenous drug users, no clear information was coming from the either the government or the medical establishment about how to stay safe. The CDC figured out transmission came only from unprotected sex or contaminated needles, but that message got lost in religious paranoia and the game of politics. Which meant as thousands got sick and died, instead of spreading the word about condoms and needle exchanges, America freaked out about kissing, touching, even passing AIDS on a toilet seat.

PART 2: SILENCE = DEATH

Soon, the potluck group didn’t want to just talk. They wanted to make something. They all had backgrounds in visual arts, graphics, and even advertising and marketing.

So they decided to make a poster, a powerful tool in a vibrant poster city like 1980s New York. A poster could be pasted up onto every construction site, every community board, every space they could think of. In a pre-internet world, a poster would be a powerful way to not only express their anger and grief, but also reach out to others with that anger and grief.

Around this time, conservative columnist William Buckley wrote a column for the NY Times where he proposed that all AIDS victims be tattooed on the arm and buttocks. As often happens in the lunacy of today’s media environment, the idea actually gained traction.

One of the members of the potluck group had recently visited Dachau, the Nazi concentration camp. And he knew that during the Holocaust, queer people were marked with a pink triangle, and systematically executed.

After a long creative workshop, the team produced a poster that was almost all black. In the center, a pink triangle. At the bottom, in huge letters, were the words “Silence = Death.”

The team paid for the poster to be reproduced and plastered over as much of the Village and key spots in the city. They wanted it to be a signal, a symbol, and a sign to take action.

Not long after the Silence=Death posters went up, in early 1987, the potluck group attended a speech from activist Larry Kramer. Other small political groups were also in attendance, and some started talking about these posters they were seeing around the city. Avram and the group admitted it was their work. They received a round of excited applause.

And suddenly, everyone started discussing the creation of a new group dedicated to AIDS protests and action. They called it ACT UP.

PART 3: ACT UP

ACT UP is the truly excellent acronym for AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power. Their goals were protests and demonstrations that hit at the centers of power, to drive action where there was none.

And from the start, they used the creative work of the potluck group, soon to be named Gran Fury.

In their first protests, ACT UP produced the Silence = Death message everywhere – placards, t-shirts, buttons, signs. And they encouraged Gran Fury to do more.

In the 1987 pride parade, filled with floats advertising local cabarets and bars, with stripped-down men dancing to club music, Gran Fury members Mark Simpson and Michael Nesline decided to stand out.

They drew the theme of Silence=Death further, and constructed a float to look like a concentration camp. They strung barbed wire between two-by-fours, encircling ACT UP members that wore their pink triangles. They set up a guard tower, with a man in a Reagan mask pointing and laughing at the camp. The scene was completed with ACT UP members in masks and gloves, like police officers were doing at the time, to hand out flyers about the next ACT UP meeting.

The float was followed by a small group of ACT UP members, shouting “ACT UP, fight back, fight AIDS.” And as the float passed through the Village, throngs of spectators joined them. By the end of the parade, the tail spread over six blocks.

And at the next meeting, hundreds of new people showed up, ready to fight.

Shortly after the parade, Mark, Michael, and new members Donald Moffatt and Tom Kalin worked on a museum street window display. They conceived of a mock trial they called “Let the Record Show.” They made placards representing Reagan and a member of his HIV commission, Buckley of the tattoo column, Jesse Helms who shouted for quarantine, Jerry Falwell of evangelical fuckery, and an anonymous surgeon. They made concrete slabs with their worst and most homophobic quotes – or in Reagan’s case, an ellipsis to show his silence. They topped it all off with the pink triangle, and a running news ticker with Silence = Death.

In 1988, as George H.W. Bush was running his presidential campaign on the phrase “read my lips: no new taxes,” Gran Fury made posters that showed men kissing, with the headlines Read My Lips. Text below reminded viewers that kissing did not pass AIDS.

Later, they made a massive bus ad featuring three couples kissing – two gay men, two lesbian women, and a straight couple. The text said “Kissing doesn’t kill: Greed and indifference do.”

There was more. More posters, more ads. Designed to shock, to provoke, to excite. Over the next few years, Gran Fury made a number of projects:

There was a fake New York Times front page showing the actual news.

Posters and painted handprints saying leaders had blood on their hands.

Fake dollar bills that ACT UP rained down on the NYSE, with messages protesting the astronomical price of new AIDS treatments, saying “fuck your profiteering.”

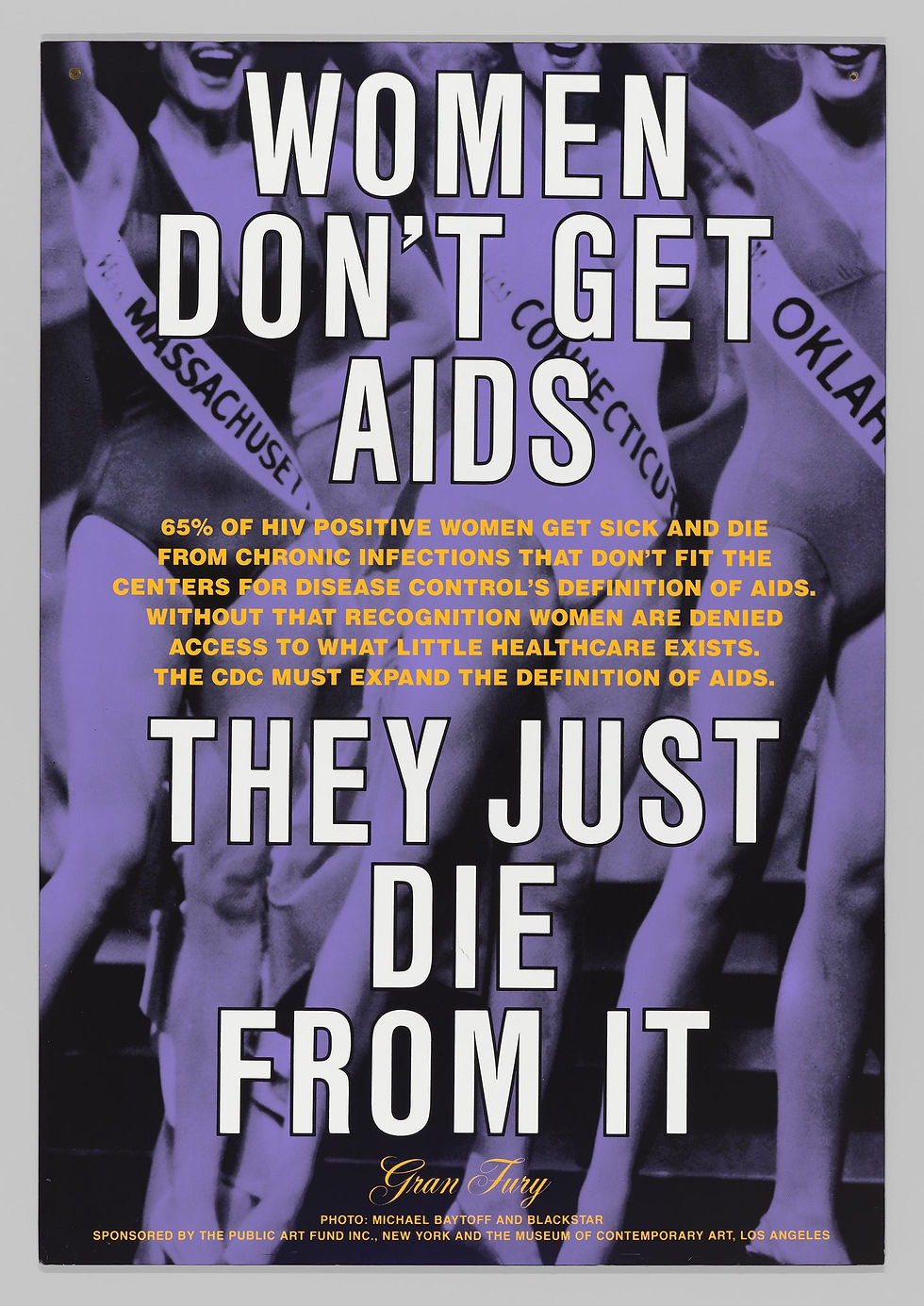

Signs to accompany a takeover of the CDC, demanding they expand the definition of AIDS to straight women, infected by closeted men: “Women Don’t Get AIDS, they just die from it.”

And as the years wore on, and deaths continued to take ACT UP and Gran Fury members, they even donated their bodies, asking that protestors carry their coffins through the streets.

PART 4: PROPAGANDA

Jack Lowery wrote the comprehensive history of Gran Fury, called It Was Vulgar and It Was Beautiful. He says ACT UP is perhaps the most well-branded protest movement ever, because of Gran Fury.

The artists thought in terms of advertising and marketing, in how people would see not only the protesters, but every queer person. Many of them came from advertising agencies or marketing, after all.

Gran Fury let the press help spread their message, simply by reporting the news on TV and in the papers, their t-shirts and banners on display. But they also placed their work directly where everyday people would see them: billboards, subway stations, buses.

As their work popped up everywhere, it was clear the members of Gran Fury thought of their posters, banners, and performance art as more than messaging, more than advertising. It was propaganda, designed to sway hearts and minds.

Instead of thinking that kissing spreads AIDS, understand that it doesn’t. Instead of thinking women don’t get AIDS, understand that they do. Instead of staying quiet or going back in the closet, speak out, even if it’s the last actions you take in life. And instead of thinking queer people deserve AIDS, understand empathy.

PART 5: IMPACT

It’s often hard to measure the impact of art. But because Gran Fury was tied so closely to an organization dedicated to action, there were clear wins.

Listen to this clip of Sara Schulman, author of Let the Record Show, in a 2021 interview.

Beyond these massive shifts in policy and perception, Gran Fury members often heard of personal individual impact of their work.

That’s one of the beautiful things about art as resistance. It helps you see yourself. It helps you save yourself, even in the midst of moments that try to destroy you.

CONCLUSION:

What can we learn from Gran Fury? What can we do as creative people in this fucked-up world?

Because we are all creative. We can all finds ways to resist.

Gran Fury work wasn’t necessarily about artistic excellence. Every member took pride in their work, and brought some artistic experience to the work. But the goal wasn’t to create work that would be shown in galleries, or spoken of as artistic mastery.

The goal was to speak directly to people. Gran Fury wanted to shift how queer people were seen. They wanted to help drive movement to help queer people survive. So they used the resources they could find, called in the favors they could, made the work that wasn’t perfect, but it was good enough.

And perhaps most importantly, they gave themselves a way to transform their grief and anger, to channel their pain. To not just survive, but to live.

For me, the lesson from Gran Fury is that. Art can be an extremely powerful tool of resistance, and change, especially paired with a movement. But it can also be a life-saving tool for the creators themselves.

There’s another lesson here. Progress gets pulled back. The wild swings of public perception continued after the 80s and 90s, and here we are, forty years later, in the midst of another massive backlash. With a government that cares little for anyone that isn’t rich, white, straight. With leaders and commentators and religious organizations that preach the end of the queer community.

So here’s what we do from here:

We understand the power of using our voice and making our art for our own survival.

We find others. We look for the people we can collaborate with, create with, commiserate with.

And we go into this, into making art as resistance, as a long-term commitment to making art for a better world.

The Art of Resistance is a podcast from Rebel Yell Creative.

This episode is presented by the Des Moines Pride Center, the largest LGBTQ library in the state of Iowa. We offer unique community events and learning opportunities, along with a fascinating look at our queer history.

At the Des Moines Pride Center, our library and archives are always growing, and you can be part of it. We host library cataloging socials on the second and fourth Sundays of each month, along with author talks, history presentations, and community events that bring people together to learn and connect. Visit us as desmoinespridecenter.org to explore Iowa’s largest LGBTQ library and archives to discover ways to get involved.

SOURCES AND FURTHER READING:

It was Vulgar and It Was Beautiful: How AIDS Activists Used Art to Fight a Pandemic, Jack Lowery

Acts of Resistance, Amber Massie-Blomfield

ACT UP: Target City Hall, WNBC News 4 New York: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fA7op98oVuM

Reagan Administration's Chilling Response to the AIDS Crisis: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yAzDn7tE1lU

The Life-Saving Legacy of HIV/AIDS Activist Peter Staley | Legendary | NowThis: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Eow4hcwoEjg

United in Anger Trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X4ZacAyc4b8

Avram Finkelstein: Silence=Death: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7tCN9YdMRiA

Gran Fury Panel at NYU Steinhardt, February 2012: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sgi1sms9gwo and

How ACT UP Flipped the Script on AIDS and Gay Rights: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y3rH8q9Q-mQ

Comments